FinTech and Financial Inclusion in China

HKUST IEMS Thought Leadership Brief No. 20

SHARE THIS

Key Points

- The government’s 2016-2020 financial inclusion plan explicitly encourages digital technologies. Over 95% of China’s on-line population of 731 million, accesses the internet through mobile devices.

- Market euphoria should be tempered by the reality that the explosive growth in China’s fintech has occurred in a regulatory void.

- Nearly 65% of P2P platforms in China are no longer operational due to bankruptcy or fraudulent practices.

- It remains unclear how much authority the new Financial Stability and Development Committee will have in mitigating financial risk.

Issue

In 2005 the United Nations recognized “financial inclusion” or “inclusive finance” as a development concept that denotes access and use of financial services, including credit, savings, and insurance. China regards financial inclusion (puhui jinrong, 普惠金融) as important for achieving a “moderately prosperous society” (xiaokang shehui, 小康社會), as indicated in the State Council’s Plan for Promoting the Development of Financial Inclusion (2016-2020). This national strategic plan was approved by the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, which is chaired by President Xi Jinping.

Compared with other countries in the region, China has a relatively high level of financial inclusion in terms of savings deposits in formal financial institutions. The World Bank’s Global Findex database indicates that 79% of China’s adult population in 2014 had accounts in a formal financial institution, which is 10% higher than the regional average of 69%.

In absolute terms, however, there are still 234 million unbanked adults in China. Significant room for progress in eradicating financial exclusion remains. The sectors of the population with the lowest levels of financial access include rural households (small-scale farmers, livestock raisers, fishermen), women, migrant workers, the unemployed, and laid- off workers. Micro and small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) also face an acute financing gap. China’s state-owned commercial banks are reluctant to lend to private MSMEs due to their stringent collateral and credit history requirements, political preference for lending to state-owned enterprises, and the high transaction costs of processing large numbers of small, short-term loans.

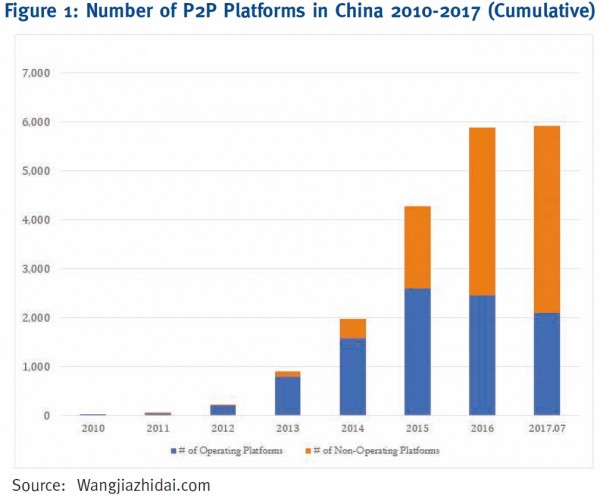

It is in this context that China’s financial entrepreneurs have turned to new technologies —especially software and digital platforms—as a more efficient means to provide financial services to private individuals and MSMEs. Increasingly popular forms of “fintech” include mobile payments, money transfers (remittances), on-line lending, and crowdfunding. The exponential growth in peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms since 2007 represents a particularly dynamic market response to the financing gap faced by private individuals and entrepreneurs. [Figure 1.] P2P websites bypass the banking system by posting projects/businesses in need of funding. These projects attract investors who seek higher returns than the low interest rates (approximately 1.5% per annum) offered by banks on savings deposits. By July 2017, there were 5,029 P2P platforms with over RMB 1.09 trillion (US$162 billion) in loans outstanding. This is over ten times the level of P2P lending only two years earlier.

Analysis

Given the tremendous market demand for web-based services, to what extent can fintech promote financial inclusion in China?

Fintech in general has the potential to serve unbanked and underbanked populations more efficiently than branch-based commercial banking. While traditional brick and mortar banks favor densely populated urban centers, those living in remote rural areas are less likely to have physical access to financial institutions. The introduction of branchless banking and digital technologies that bypass banks altogether can greatly enhance access to financial services.

Kenya’s M-Pesa payment system for example, enables users to deposit cash on their mobile phones in retail outlets and transfer funds through PIN-secured SMS text messages. Operating in Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe, M-Pesa now has the most extensive mobile-phone based financial service network in the world. Newly-established remittance agencies such as World Remit and Azimo are similarly offering mobile-phone based services, which has reduced the fees to a fraction of that charged by traditional outlets.

China possesses an increasingly robust infrastructure for deploying these technologies towards financial inclusion. The People’s Bank of China reports that over 90% of villages already have ATMs or point-of-sales (POS) devices through retailers or nonbanking financial institutions that enable rural residents to withdraw cash. Digital modes of financial inclusion are promising as well. Over 95% of China’s on-line population of 731 million accesses the internet through mobile devices, especially phones. An estimated 66% of rural households in China have at least one smartphone. As such, the government’s 2016-2020 financial inclusion plan explicitly encourages digital technologies “to offer micro-deposits, microloans, payments, settlements, insurance and other types of financial services to agricultural producers.”

The government’s strategy holds promise, as fintech in China has developed more rapidly than in other countries in the region, including Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore. Although state-owned telecommunications and banking institutions have started incorporating mobile technology in their products, it is China’s private fintech companies that have made the most significant inroads in expanding the market for their web-based services. Alibaba and Tencent’s third-party payment companies, AliPay and TenPay/WeChatPay, have over 475 million and 600 million subscribers, respectively, who use their platforms for online purchases. Digital payments—rather than debit and credit cards—account for the preponderance of non-cash payments in China. Meanwhile, P2P platforms not only serve MSMEs’ need for commercial credit, but also lend to individual consumers. Shoppers on Alibaba.com and JD.com can take out small loans from Alibaba’s financial unit, Ant Financial. The latter also operates the world’s largest on-line money market fund, Yu’E Bao, which manages over RMB800 million in assets and has over 300 million investors.

Taken together, these private sector initiatives demonstrate that China’s tech-based financial inclusion can be highly profitable. In 2015, Yirendai.com became the first internet finance company to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The following year, China’s fintech industry attracted US$10 billion in investment, which represented 90% of the total investment in Asian fintech companies, and over half of venture capital in fintech globally.

Recommendations

The combination of government support for financial inclusion, private entrepreneurship in fintech, and the international investment community’s bullish response to China’s fintech sector is encouraging. From the perspective of promoting financial inclusion and social stability, however, market euphoria should be tempered by the reality that the explosive growth in China’s fintech has occurred in a regulatory void.

Above all, lax regulation means that fintech products pose higher risks to consumers, investors, and the unbanked than traditional financial services. Until recently, literally anyone could launch a P2P website and start mobilizing funds from eager investors. In the absence of adequate regulation, nearly 65% of P2P platforms in China are no longer operational due to bankruptcy or fraudulent practices. Ezubao’s collapse in 2015 was a high-profile example of the risk associated with free-wheeling fintech. Within a year of its establishment, the online finance company mobilized US$7.6 billion from nearly 900,000 investors by offering “investment products” that turned out to be fake. Thousands of P2P platforms are no longer operational due to mismanagement and/or outright fraud.

A cognate gap in consumer protection can be seen in predatory lending to female college students. In mid-2016, domestic and international media revealed that various P2P platforms, including Jiedaibao.com, were using nude photos of female borrowers as collateral for their loans. Dubbed “naked loans” (luotiao jiedai, 裸條借貸), the platforms coerced students into taking out additional usurious loans when they were unable to make payments by threatening to publish their photos on social media, and send them to their friends and family. The China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) has since banned unauthorized financial institutions from lending to students; and the China Construction Bank and Bank of China have introduced consumer loans on university campuses. Nonetheless, the naked loan scandal remains a cautionary tale about the risks posed by the use of fintech in promoting financial inclusion.

Following widespread P2P failures and digital financial malfeasance, the CBRC has limited individual borrowing from P2P platforms to RMB200,000 (August 2016). Furthermore, platforms are now required to deposit invested funds into commercial banks; verify the source of invested funds by both creditors and debtor; and provide daily reconciliation of transactions by platforms and banks (February 2017). In August 2017, a new Financial Stability and Development Committee under the State Council was proposed to mitigate seven types of system financial risk, including “bad loans, liquidity management, shadow banking, external shocks, the real estate market, government debt, and internet finance.” It remains unclear, however, how much authority and implementation capacity the new committee will have as the regulatory environment for fintech continues to evolve.

Finally, the government’s effort to establish a national “social credit system” (geren chengxin tixi, 個人誠信體系) is intended to provide credit scores for consumers and MSME owners who lack collateral and/or credit histories. Although such a system could promote financial inclusion, the initiative has raised concerns that data collected from social media and mobile records will also enhance the regime’s capacity for social control and repression. Fintech is double-edged, with implications that extend beyond financial inclusion.

Get updates from HKUST IEMS