Understanding the Globally-Mobile, Young Consumers from the Emerging Markets

HKUST IEMS Thought Leadership Brief No. 19

SHARE THIS

Key Points

- In 2016, 544,500 Chinese students studied abroad. 91.49% among them were selffunded.

- In the academic year of 2015-16, about one-third of the 1,043,839 international students in the U.S. were from China.

- These international students are not necessarily the early adopters of Western trends, as they may refer to their Chinese social networks and tend to seek brands that are overpriced in China but relatively affordable in the U.S.

- Overlapped interpretations of upward mobility and outbound mobility are observed among the informants of the present study.

Issue

Economic development in emerging markets (EMs) has expedited social mobility change, true for both vertical (status change) and horizontal (identity change) trajectories. Yet scholarly discussions focus on impersonal, macro-societal social mobility rates, with few exploring what they mean for the person. In terms of consumer behavior, a person’s changing identity and their interpretation of their social mobility experiences could be as important as how their social position shifts are defined on paper. Additionally, demographic predictions fail to predict how consumers understand and react to their changing social positions, thanks to the identity strain from social mobility.

This Brief provides some business insights by characterizing EM consumers through their social mobility experiences. Specifically, it will discuss the identities and consumption habits of young consumers from China through their continuous interests in pursuing higher degrees overseas, which implies upward as well as outbound mobility.

Discussions regarding EM consumers usually revolve around their awareness of how the local market is different from the global ones and their corresponding shopping preferences. For example, thanks to the perceived price and product differences, Turkish consumers tend to feel that they are excluded from the “global middle,” a wide imagination of the world standards in places such as the U.S. and Europe. As a result, these consumers are interested in e-commerce, counterfeits, and oversea shopping in order to keep up with the world. That is to say, global consumerism has shaped consumers’ practices in the local market. However, with regard to how consumers negotiate with the global and local market norms, their own cross-cultural mobility experiences are often ignored.

Assessment

In some fields, such as social policy, objective, external variables prevail to ensure the efficiency and fairness of policy enforcement. For example, subsidies should be allocated on those who live under the poverty line (i.e., absolute poverty), with less consideration on individuals’ subjective feelings of deprivation (relative poverty). However, in the field of consumer studies, how consumers see themselves may be as important as how they are defined by marketers. Their shopping decisions are not simply affected by their needs and discretionary incomes, but the lifestyle with which they identify.

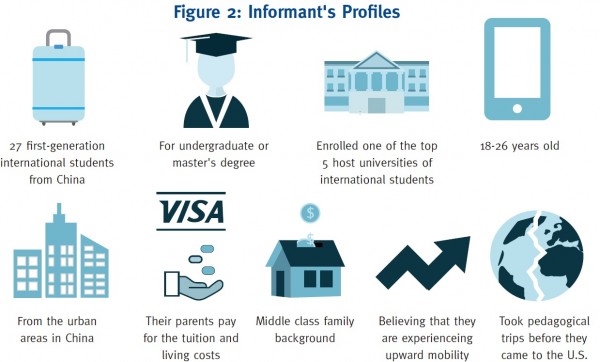

A general perspective in the popular media on the consumption of international students often associates these youngsters with the “rich second generation” or the “Great Gatsby Generation” to either imply or explain their extravagant, hedonic shopping. In 2016, 544,500 Chinese students studied abroad according to the Ministry of Education, and 91.49% among them were self-funded (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, March 1, 2017). Although international students can be assumed to be a privileged group with economic security, based on the interview data collected in 2016, some of their shopping preferences are associated more with their globally-mobile experiences than their strong spending power

They seek progressive, cosmopolitan meanings in global, mass brands.

The international students from China interviewed (“informants” thereafter) perceive their outbound mobility to be highly overlapped with upward mobility, i.e., although they usually subscribe to an overgeneralized social class consciousness, they tend to believe that they are “moving up” or “moving ahead” through the international relocation. Associating these two forms of mobility may be due to the unclear social stratification in China, where social class cannot be precisely determined by specific demographic variables (Miao, 2017), as well as the informants’ decent family backgrounds that leave little room for intergenerational upward mobility, which is traditionally measured by income, education, and occupation.

As a result of such “moving out as moving up” perception, the informants tend to stress that they are cosmopolitan consumers who are informed of the market norms across various cultural contexts. As Holt (1998) suggested, such particularities are better signaled in how they interpret their shopping, instead of what they buy. In other words, while these young consumers seem to share similar tastes with their local peers, the meanings behind their common choices may diverge. For example, the informants do not show unique interests in certain media content, but they emphasize that their access to this content is informed by progressive social norms, such as the protection of copyrights. The reason why channels like Netflix become popular among informants is not simply about the ad-free contents, but the “advanced” value it represents that cannot be accessed through watching pirated contents.

They align themselves with the EM “middle.”

The informants’ cosmopolitan signaling is China-oriented, as they often “consume” the cosmopolitan meanings that have already been “endorsed” in China. Rarely would they explore and consider products and practices that are only recognized in the U.S. but unfamiliar to Chinese consumers. On the contrary, they frequently refer to the product reviews, bloggers, and newsletters targeting Chinese consumers. As a result, the informants prefer shopping in the U.S. for those global brands overpriced in China, since they are perceived as “high-end” and aspirational despite their affordability in the U.S. Compared to other EM consumers who try to align with the world standard, the informants counter-align themselves with the middle in their home country even when they are exposed to the “authentic” consumer society. Their shopping is thus mediated by their sensibilities of the popular cosmopolitanism.

Such strategic shopping differentiates the informants from other globally-mobile consumers such as global nomads, immigrants, business elites who constantly travel, and expatriates. The informants’ U.S.- based but China-oriented consumption is assumed to be associated with their plan of returning home-they make the most of their temporary stay in the U.S. to signal cosmopolitanism to the Chinese community, where their past and future identities are fostered.

Recommendations

Young consumers from China may not subscribe to a clear, westward social stratification framework, but they define their social mobility alternatively to signal their “moving up” through international relocation experiences. While studying abroad, these informants from China do not aim to be the early adopters of the latest trend, but rather refer to their original, Chinese community so as to ensure that their cosmopolitan signaling is meaningful and familiar to their local peers. To attract these consumers, practitioners may want to consider appealing to “familiar exoticism,” as well as a global image that has been adapted to the Chinese market. Finally, the same set of data also reveals that while the informants care about discounts, the efforts they are willing to pay to obtain a deal is low. Thus, when trying to engage the millennials, sellers may want to avoid requesting too much time and effort from them, such as long queues for a sales event or completing challenging tasks through social media to obtain discounts.

About the author

Wei-Fen Chen joined HKUST in 2016 as a postdoctoral fellow in the Institute for Emerging Market Studies, after receiving her PhD in Communications and Media from the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign. Her research focuses on consumer culture and social stratification, particularly in regard to the psychographic and demographic features and consumption practices of individuals experiencing upward/downward social mobility. She was a recipient of the Fulbright Fellowship, the S. Watson and Elizabeth S. Dunn Fellowship, and the Dissertation Completion Fellowship from the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange. Previously, she worked as a government officer in Taiwan, specializing in press liaison and media strategy.

Get updates from HKUST IEMS